Letter from Paul Atkinson to Scrutiny Committees, Healthwatch Committees, Health and Well-being Boards and the Clinical Commisioning Group of the NE London Integrated Care Board area

For the attention of members of the North East London Scrutiny and Healthwatch Committees, and Health and Well-Being Boards

Talking Therapies in the NE London ICB area

I am writing as a Tower Hamlets resident and a psy professional with decades of experience, to ask that you turn serious attention to the accessibility of talking therapy in our communities in the NE London ICB region.

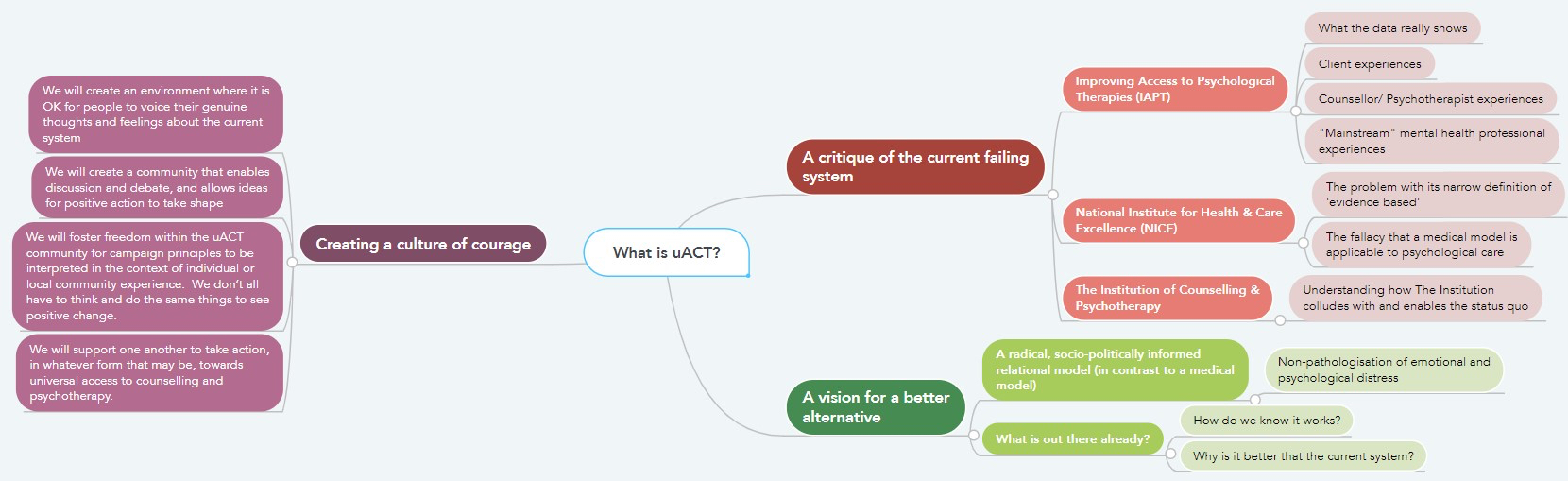

There is a growing crisis, with ever-more people suffering from common mental health distress. At the same time, the NHS Long Term Plan includes promises to reorganise community mental health services. For both reasons, I suggest it is now time for a critical review of the primary care psychological therapies currently being provided by the NHS in the NE London boroughs.

In NE London, as elsewhere, NHS Talking Therapies (formerly known as Improving Access to Psychological Therapies, or IAPT[1]) has for many years been providing an inefficient and unsatisfactory service, supported in part by misleading statistical evidence of its efficacy. Historically, IAPT has not been subjected to independent audit, and its claim to provide a successful, innovative, adult mental health service is neither properly accountable and transparent, nor, in fact, evidence-based. I explain below how this plays out in NE London.

Talking therapy can definitely be brought closer and respond more flexibly to different communities in need of psychological and emotional support. But, to achieve this, the monopoly of NHS Talking Therapies (NHS TT) in primary care will have to be undone. I have set out some of the alternatives in this paper.

- NHS Talking Therapies meets none of its NHS targets

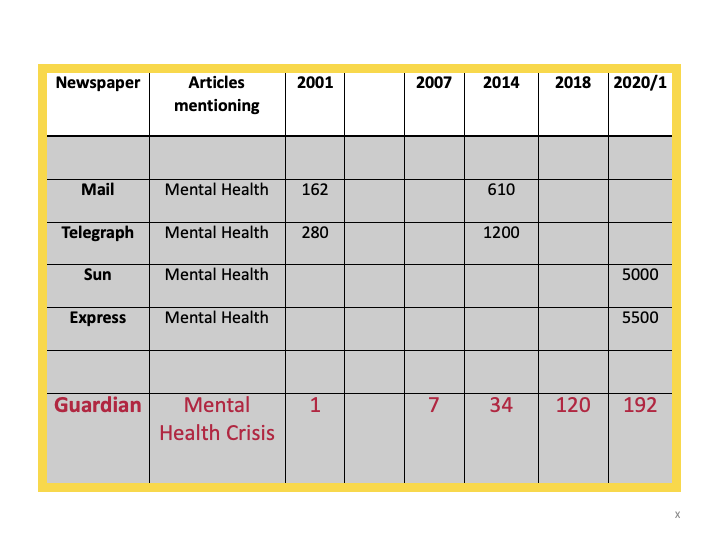

The NHS Long Term Plan gives Talking Therapies (TT) three targets: on access, waiting times and recovery.[2]

- It is asked to give access to 25% of the ‘adult community prevalence’ of common mental health disorders (CMD).

- 75% of referrals should have their first treatment session within six weeks.

- 50% of its patients should recover.

It does none of these.

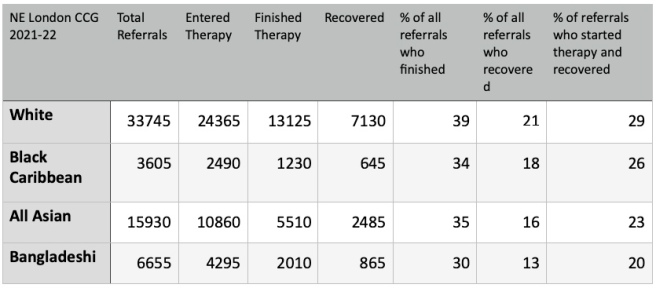

- The adult community prevalence of CMD in the NE London ICB area is around 320,000 people.[3] IAPT gave access to 48,800 adults in 2021-22, i.e. just over 15% of the prevalence – well below the 25% target. Only about half of the 15% ‘recovered’.

- IAPT in NE London apparently met the waiting time target in 2021-22, but achieved this by calling the assessment session the first session. About half of all referrals dropped out after this one session. Of the remainder, half waited between 6 to 12+ weeks for their second session.[4]

- The claimed recovery rate of 50% applies to people who finished rather than entered a course of treatment. The recovery rate[5] of people who entered therapy was 25% in 2021-22. There is also virtually no follow up after treatment to find out whether recovery lasts for any length of time. In NE London, 1% of referrals who finished therapy were followed up after 6 months.[6] There are reports of NHS TT staff nationally being pressured by management to falsify their outcome statistics.[7]

2. NHS Talking Therapies is not cost-effective

The cost of NHS TT sessions is not in the public domain, as far as I have been able to discover. But we can do a very crude calculation.

In 2021-22, IAPT funding for NE London was £36.2 million. The median duration of a session that year was 52 minutes, and for a finished course of treatment it was 310 minutes or 6 sessions. If we divide the spend by the number of people who finished a course of treatment (25,275), the cost per session was just under £240.[8]

If we use this admittedly crude measure, NHS TT’s claim to cost efficiency doesn’t hold water. In the Counselling Directory[9] (the largest directory of independent practitioners in UK), over 60 qualified, self-employed, insured and professionally accountable independent practitioners based in east London are currently offering counselling and psychotherapy for under £40 per session.[10] Even allowing for NHS TT’s high drop-out rate of 50% of clients who started therapy, £240 could potentially buy for each patient at least three times the number of sessions.

3. NHS Talking Therapies has an exceptionally high drop-out rate

Why did only 25,275 out of 72,000 referrals in 2021-22 finish a course of IAPT therapy in NE London? What happened to the other 65% of our residents who, for one reason or another, had expressed concern about their mental health?

According to their annual performance data, IAPT services in NE London are more or less average for England as a whole.[11] But, by any comparisons, the dropout rates are exceptionally high.[12]

So, what is the problem with NHS TT?

4. One size doesn’t fit all – the denial of care

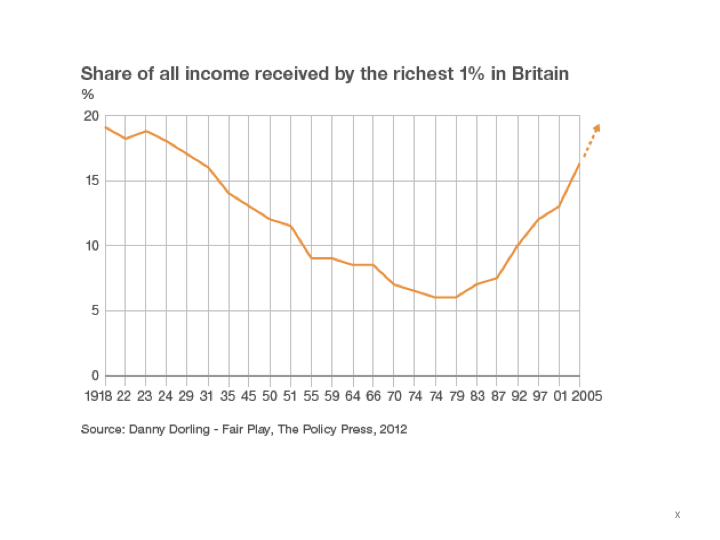

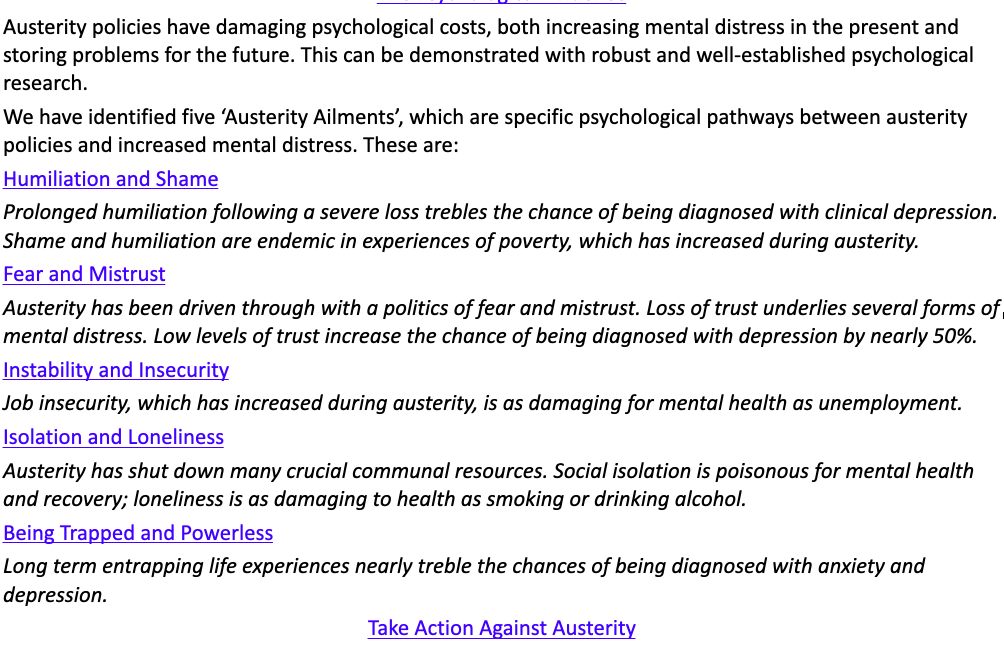

NHS TT is a political and ideological project. It is organised around variations of a single psychological theory and practice – cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). For NHS TT, CBT has been adapted to the requirements of New Public Management in terms of measurable costs and targets, standardisation of practice and data collection, efficient through-put and the prioritisation of utilitarian values.

It has virtually exclusive approval by NICE as evidence-based psychological therapy provision – a status which has been challenged consistently as manufactured and politically protected.[13] Shortly after its introduction in 2008, it supplanted most other counselling and psychotherapy provision in primary care.

Many therapists who are not part of the NHS TT workforce do not recognise its practice as “real” psychotherapy and counselling, in that it does not base itself in the co-creation of a therapeutic relationship and alliance. In many ways, NHS TT offers a technique rather than a relationship; a didactic rather than a therapeutic process.[14] Patients are “told” how to think.

NHS CBT is a model of therapy[15] that certainly helps a proportion of clients with distressing spirals of negative thinking and behaviour. It can be transforming to feel heard, to have the experience recognised and put into words, to have our emotional world taken seriously. For many people it will be their first experience of any kind therapeutic attention. This, in itself, is an admirable achievement of scale by the NHS TT project.

But, for many people and for all kinds of reasons, the NHS TT approach to emotional distress will either not make a connection, or will fail to travel deeply enough to carry meaning for the client. Dropping out is a fact of life for all therapy work, of course, but NHS TT’s lack of relational flexibility, the rigidity of its commitment to an instrumental “assembly line” methodology[16] and its strict adherence to very short-term work[17] puts significant limits on the number of clients who will engage and find it helpful.[18] Moreover, the NHS TT workforce nationally is itself suffering mental health problems under the pressure of delivering “assembly line” therapy.[19]

The service’s monopoly over psychological therapies in the NHS is not based on patient care. In fact, in this period of increasing privatisation and monetisation of health care, it appears to be a forerunner of the politics of denial of care via the rhetoric of data, efficiency and social management.

5. NHS Talking Therapies fail to address inequalities of mental health care

The dominance of NHS TT is an obstacle to responding more effectively to common mental ill-health in our diverse communities.[20] The limitations of the service’s standardised approach are demonstrated, for example, in its limited engagement with mental health inequalities around social deprivation, race and gender.

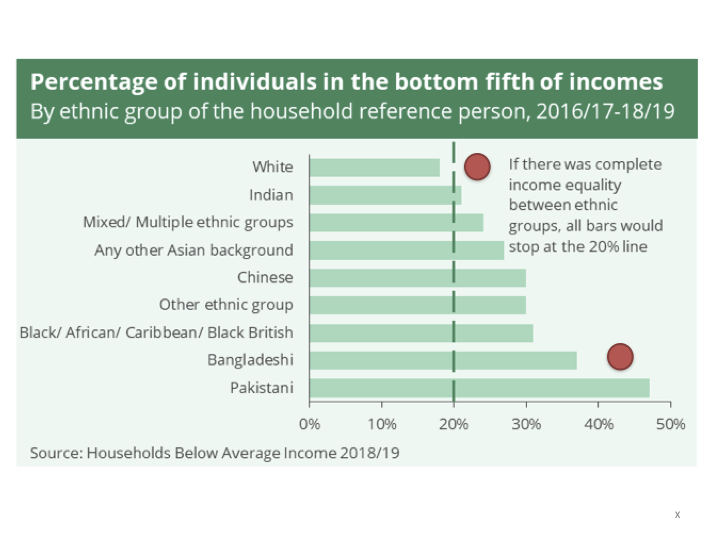

For example, 72% of less socially deprived referrals who entered therapy in NE London in 2021-22 finished a course of treatment, and 38% recovered. Among more deprived referrals, only 57% completed course of therapy and only 26% recovered. Barking and Dagenham, Hackney, Tower Hamlets and Newham are among the most deprived boroughs in London.[21] In Tower Hamlets, in 2019-20, only 18% of the more socially deprived who entered therapy recovered.[22]

Far more women than men access the service. In 2021-22, 70% of all referrals in NE London and 80% of people who finished a course of therapy were women.

Inequalities of access by ethnicity are striking. My home patch in Tower Hamlets has the largest Bangladeshi population in the UK. Comparing referrals from the Bangladeshi and the white communities in NE London, 36% of all Bangladeshi referrals dropped out before starting any therapy, 47% who did start went on to finish a course of treatment, and only 20% who entered therapy achieved recovery. The same figures for the white population were 28% initial dropout, 54% finished, and 29% recovered.

6. Talking therapy and rethinking community mental health

The NHS’s Community Mental Health Framework for Adults and Older Adults (2019-21)[23] is an ambitious report, promising integrated care in local communities for people suffering severe and common mental health difficulties. But anyone who has been involved with NHS mental health services or who has been campaigning over the years to resist the process of privatisation, outsourcing, defunding, digitalisation and staff reduction will know that we are in a political environment that will not support most of the Framework’s ambitions with the funding and staffing it requires.[24]

Whatever does end up being introduced will almost certainly see the existing NHS TT service being tasked with delivering most of the promised “innovative”, “integrated”, “effective” care. But what does this mean in practice? In fact, NHS TT is highly privatised and heavily dependent on computerised self-help guides and wellbeing apps. It rations access to its services by using diagnostic algorithms and “clusters of unsuitability”. It gives its therapists AI-determined optimal scripts for use with patients.[25] It is one of the few health services that has expanded steadily year on year since its beginnings in 2008.

None of this offers the best way to reach people in distress in our communities. Before yet more money is spent on our local NHS TT service, it needs to be subjected to thorough independent audit. At the moment, it represents an unacceptable waste of resources, while being presented as the only efficient contender in the provision of therapy for common mental health disorders.

Very many psy professionals believe that NHS TT’s approach is neither efficient nor the only contender. There are genuine, viable alternatives that are more likely to help build networks of supportive relationship in local communities.

7. We need diversity of talking therapies

There are many free and low-cost therapy providers in London, run by fully qualified counsellors and psychotherapists, that serve their local community. They are often charities whose funding is limited and precarious.[26] There are also qualified therapists providing therapy and therapeutically-informed support in many community projects.

For example, I have been working for 4 years offering free psychotherapy at my local community centre in Poplar. I am doing individual weekly sessions with an open-ended relational approach. Many of my clients have chronic mental health difficulties but no therapeutic support from local services. I am developing emotional support groups for local residents and a reflective practice group for community workers who are feeling overwhelmed by referrals from GP social prescribing – a Common Mental Health Framework strategy. I have been approached by a local primary school to start a support group for its parents.

I am a founding member of the Free Psychotherapy Network.[27] Many FPN therapists have similar local arrangements with community projects. Our members are involved in a therapy centre at an urban farm in Hackney, free counselling in community centres in Ilford, therapy and emotional support with the homeless and substance misusers in Waltham Forest, work with primary schools and a parent/infant support service in Leytonstone, and a dozen charities offering low-cost counselling in NE London. The picture is similar in other parts of London and the UK generally. At the moment, these projects are small and have minimal funding. With the right support they and projects like them could grow rapidly.

Scores of experienced counsellor and psychotherapist colleagues are interested in working for the common good in community settings, but, unlike me, they cannot all afford to work without funding. Rather than focussing exclusively on funding the expansion of NHS TT with all its limitations, why can we not develop more imaginative and flexible initiatives at a far lower sessional rate? These initiatives could include providing individual and group therapy in community centres, schools and colleges, as well as acting as support workers for residents and the communities around them. The practitioners involved would organise their own supervisory practice and shared peer reflection, make relationships with adult and young people’s mental health care services, community project teams, local schools, GP practices and social prescribers, substance misuse services, homeless groups, and so on.

This kind of model puts therapists much closer to the everyday lives and needs of people, are more open to negotiating those needs with communities and can be an integral part of a bespoke range of ongoing resources and support.

New funding would be great. But there is also money in the system that can be repurposed. We already know of a low-cost counselling service in the Newcastle area that is being partially funded by Primary Care Network social prescribing budgets to provide more relational counselling for clients defined as “unsuitable” by the local NHS TT services. There is even more potential for lasting change if a proportion of local NHS funding that is currently going to our homogenised TT services could be redirected towards the community to deliver on the promises in the Long Term Plan. These NHS budgets could be held by Primary Care Networks, or by individual GP surgeries (who often employed counsellors before the introduction of IAPT) – bringing funding as close as possible to the communities that need to be served.

If the Common Mental Health Framework is to mean anything other than a smoke-screen of words and tech, the role of employed professionals, and their energy for making relationships of different kinds, has to be massively scaled up. Apps and social prescribing to already overloaded and under-funded charities and local authority services is not going to lift our communities out of the mental health crisis we are in. People and relationships built on trust over time are central to any substantive change in the emotional wellbeing of our NE London communities.

8. Audit and scrutiny

NHS TT is regularly praised by its leadership as a major national and international success story.[28]

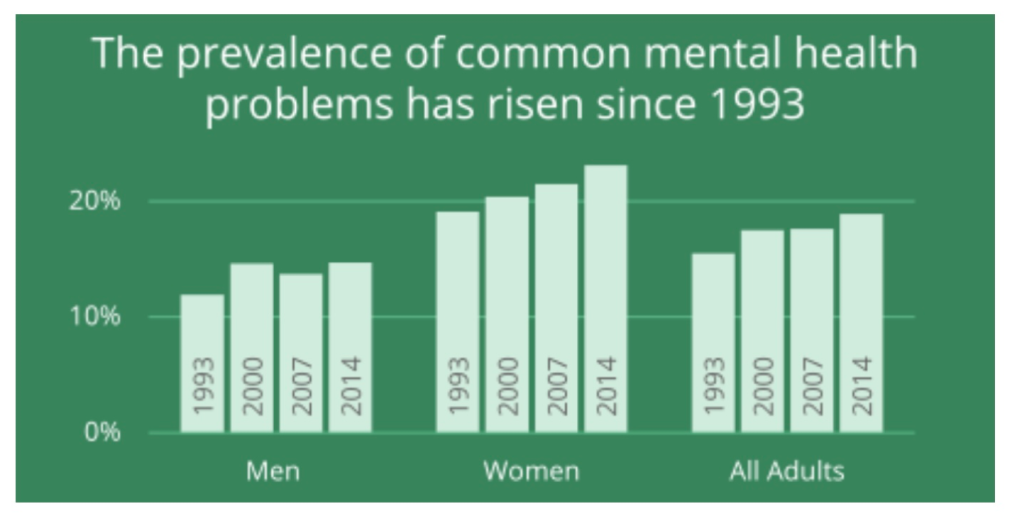

However, it is not independently audited and relies on the avalanche of its own data collecting to justify and maintain its claims to be a successful, evidence-based service. Many critical reviews of its data suggest a different picture.[29] In terms of its access rate, its drop-out rate and its recovery rate, its performance is poor, and far from cost-effective.[30] As far as the quality of the therapy it provides is concerned, there is no evidence that any positive therapeutic benefit is effective over time. Nor is there any evidence that the prevalence of common mental health problems in the UK population has declined in the decade since the service was rolled out – on the contrary.[31]

I am asking you as members of Scrutiny, Health and Wellbeing, and Healthwatch Committees to give serious consideration to the reality of failings and inefficiencies hiding in plain sight in the spreadsheets of NHS TT reports. In the middle of what seems to be an ever-deepening crisis of mental health, with so much political pressure for cuts in NHS services and staff, and in particular the decades of underfunding and denial of care in mental health care, it is time to attend with the utmost urgency to the need for dramatic improvements in the services available to our residents in North East London.

I look forward to a response from your committee.

Paul Atkinson

Professional Member of the Philadelphia Association

Member of Socialist Health Association/Keep Our NHS Public London Mental Health Group

Member of the Free Psychotherapy Network

[1] Where I refer to the data reports for NHS Talking Therapies before the name change in Feb 2023, I will use the term IAPT.

[2] https://mentalhealthwatch.rcpsych.ac.uk/local-area-reports/detail/north-east-london

https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/the-iapt-manual-v5.pdf pp 36-40

[3] Population of NE London ICS – 2,000,000; adult population = 1,600,00; adult prevalence of common mental health disorders @20% = 320,000 (see https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/common-mental-disorders/area-search-results/E39000018?place_name=London&search_type=list-child-areas); NHS TT target is to give access to 25% of the adult prevalence of common mental health disorders = 80,000.

[4] https://www.bacp.co.uk/news/news-from-bacp/2019/5-december-long-waiting-times-for-iapt-unacceptable/

[5] The definition of “recovery” and the way it is quantified by getting the client to complete a Beck inventory in every session, is a good example of the way the IAPT model has been mechanised.

[6] Some providers’ follow-up to Freedom of Information requests is also non-existent https://www.whatdotheyknow.com/request/following_up_referral_drop_outs#incoming-2084534

[7] https://hrnews.co.uk/nhs-therapists-are-pressured-to-exaggerate-success/

[8] £36.2m/25,275/6 = £238.7 For median duration stats see https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiMDk2OWUzMjEtN2YxYS00YzgwLThkMGMtMjNlZWE1MWIyMTk3IiwidCI6IjUwZjYwNzFmLWJiZmUtNDAxYS04ODAzLTY3Mzc0OGU2MjllMiIsImMiOjh9p.32

[9] https://www.counselling-directory.org.uk/search.php?search=East%20London&distance=5&session_type%5B%5D=in-person&session_type%5B%5D=online&business_type%5Bindividual%5D=on&price_min=40&price_max=40

[10] Psychological Wellbeing Practitioners (PWP) who do most of the Low Intensity work in NHS TT have a salary of between £14 and £17 per hour – https://www.prospects.ac.uk/job-profiles/psychological-wellbeing-practitioner

[11] See the March 2023 House of Commons Report for a good national overview of IAPT services – https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN06988/SN06988.pdf

[12] In my 40-year experience practising counselling and psychotherapy in independent settings, the drop out rate for more relational therapies, rather than the instrumentalism of IAPT, is likely to be closer to 10%. However, studies of dropout rates in different settings and environments of mental health services are complex and vary. By any comparisons, IAPT dropout rates are exceptionally high – see https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12888-019-2235-z,https://cpe.psychopen.eu/index.php/cpe/article/view/6695/6695.html,https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/capr.12249, https://iaptus.co.uk/2022/06/what-impacts-patient-engagement-with-mental-health-treatment/

[13] http://www.limbus.org.uk/cbt/index.html

[14] https://www.bmj.com/content/380/bmj.p464

[15] https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/the-nhs-talking-therapies-manual-v6.pdf p.13. In NE London ICB in 2021-22, there were 9920 finished courses of CBT; 6365 of guided self-help (book); 1835 counselling for depression; 1365 non-guided self-help (book); and a small number of other types of therapy – see https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiOTIyYTgyYjEtM2QxZS00YzYyLWI3YTEtZDU1NjhjNjlmYmE0IiwidCI6IjUwZjYwNzFmLWJiZmUtNDAxYS04ODAzLTY3Mzc0OGU2MjllMiIsImMiOjh9p.4.

[16] https://www.pccs-books.co.uk/articles/article/the-industrialisation-of-care-counselling-psychotherapy-and-the-impact-of-i

[17] This therapist can simply not understand how, in many cases, “courses of treatment” consist of just two sessions.

[18] https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bjc.12314

[19] https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/events/faculties-and-sigs/general-adult-psychiatry-20/research-case-reports/abeku-koomson.pdf?sfvrsn=76850f44_2#:~:text=Amongst%20the%20IAPT%20workforce%2C%20PWPs,in%20the%20mental%20health%20field2 http://www.cbtwatch.com/nhs-talking-therapies-on-the-brink/

[20] Its influence is not confined to NHS services. Its model of therapy practice has been imposed on most charitable therapy provision that relies on public and charitable funding. MIND and other major mental health charities have, in fact, become NHS-approved IAPT providers.

[21] https://centreforlondon.org/blog/deprivation-london/

[22] https://www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/charts-and-infographics/referrals-for-psychological-therapy-from-patients-in-deprive See NE London ICB survey of the scale of deprivation and mental ill-health here – https://www.northeastlondonhcp.nhs.uk/downloads/Insight/NEL-Population-health-profile-May-2022-v4.pdf

[23] https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/improving-care/nccmh/the-community-mental-health-framework-for-adults-and-older-adults-full-guidance/part-1-the-community-mental-health-framework-for-adults-and-older-adults—support-care-and-treatment—nccmh—march-2021.pdf

[24] For example, Prof Peter Fonagy, UCL and NE London ICB partner, recently wrote: “A continuing challenge lies within resources – it is estimated that if every psychologist worked 50 hours a week they would still only meet 12% of the current demand.” https://uclpartners.com/blog-post/meeting-mental-health-needs-with-innovation-and-connection/

[25] https://www.lyssn.io/press-release_trent-pts/

[26] https://freepsychotherapynetwork.com/organisations-offering-low-cost-psychotherapy/

[27] https://freepsychotherapynetwork.com/

[28] https://www.england.nhs.uk/blog/iapt-at-10-achievements-and-challenges/

[29] http://www.cbtwatch.com/clinical-commissioning-groups-ccgs-incredibly-naive-re-iapt/

[30] See NE London ICB report p.12 – https://northeastlondon.icb.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Annual_Report_2021-22_FINAL_Redacted.pdf

[31] http://www.cbtwatch.com/more-treatment-but-no-less-disorder-what-is-going-on-here/ Compare 2007,2014,2017 – https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiMmRiY2FkYmUtZDQwOS00MDNlLWEyYTktZTQ1N2RiZTNkNGM5IiwidCI6IjUwZjYwNzFmLWJiZmUtNDAxYS04ODAzLTY3Mzc0OGU2MjllMiIsImMiOjh9and https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile-group/mental-health/profile/common-mental-disorders/data